Tears of the Cosmos: Pope John Paul II’s Vision of Weeping Statues

Tears of the Cosmos: Pope John Paul II’s Vision of Weeping Statues

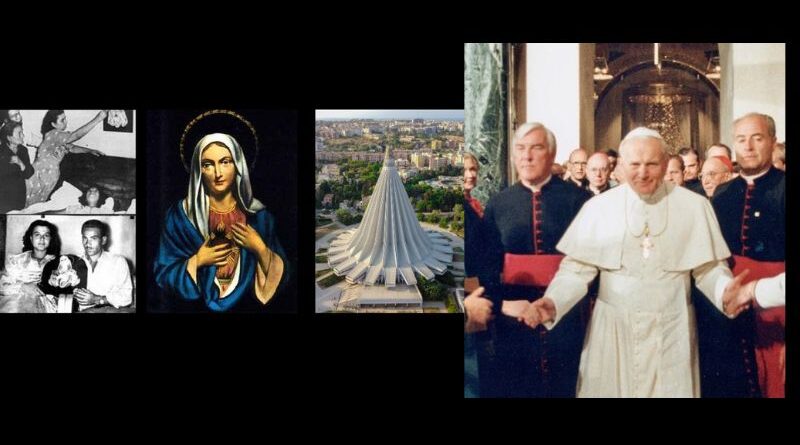

In the tapestry of Catholic spirituality, few phenomena capture the imagination as profoundly as weeping statues of the Virgin Mary—silent tears that seem to pierce the veil between heaven and earth. On November 6, 1994, during the consecration of the Sanctuary Basilica of Our Lady of Tears in Syracuse, Sicily, Pope John Paul II offered a haunting reflection on these enigmatic signs, declaring that “the tears of the Madonna belong to the order of signs” and carry a cosmic significance. His words, delivered against the backdrop of a world scarred by war and division, framed weeping statues as divine whispers of sorrow, compassion, and hope. This article delves into the Pope’s statement, its theological depth, and its resonance with events like the Seton Miracles in Lake Ridge, Virginia, where statues wept in the presence of a stigmatic priest.

The Syracuse Context: A Shrine Born of Tears

The Sanctuary Basilica of Our Lady of Tears, a towering teardrop-shaped edifice in Syracuse, Sicily, stands as a monument to a miracle that began in 1953. In the modest home of Angelo and Antonina Iannuso, a plaster plaque of the Immaculate Heart of Mary wept human tears from August 29 to September 1, accompanied by Antonina’s miraculous healing from pregnancy complications. The Archdiocese of Syracuse, with rigorous scrutiny, authenticated the phenomenon within months, and the Sicilian bishops declared it supernatural. By 1994, the basilica, designed to hold 11,000 pilgrims, was ready to be consecrated, and Pope John Paul II, a pontiff deeply devoted to Mary, journeyed to Sicily to dedicate it.

It was here, beneath the soaring arches of the basilica, that the Pope articulated his vision of weeping statues. In his homily, he said, “The tears of the Madonna belong to the order of signs. She is a mother crying when she sees her children threatened by a spiritual or physical evil.” He wove the Syracuse miracle into a cosmic narrative, linking it to other Marian apparitions—such as La Salette and Fatima—and situating it within the turmoil of the 20th century. The tears, he suggested, were not mere curiosities but profound expressions of Mary’s maternal heart, weeping for humanity’s sins, suffering, and rejection of God’s love.

A Cosmic Meaning: Tears as Divine Signs

John Paul II’s statement imbued weeping statues with a universal, almost otherworldly significance. The phrase “order of signs” evokes a celestial language, a divine semiotics through which God communicates with creation. For the Pope, these tears were multifaceted: they mourned the spiritual desolation of a world that turned from faith, grieved the physical devastation of wars—particularly the “immense slaughter” of World War II—and called humanity to repentance. He connected the Syracuse tears of 1953 to the post-war era, noting their timing alongside the rise of “openly atheistic communism” in Eastern Europe and the Holocaust’s horrors. The tears, he implied, were a cosmic lament, a mother’s cry echoing across history.

This perspective was rooted in the Pope’s broader Marian theology, shaped by his survival of an assassination attempt on May 13, 1981—the feast of Our Lady of Fatima—which he attributed to Mary’s intercession. His devotion to Fatima, where Mary’s messages warned of spiritual and global crises, informed his view of weeping statues as extensions of her maternal mission. In Syracuse, he saw the tears as a call to contemplation, urging the faithful to “stop and reflect before this sign” and respond with conversion and prayer. The cosmic scope of his words suggested that such phenomena transcended local contexts, speaking to the universal Church and its mission in a fractured world.

Resonance with the Seton Miracles

The Pope’s statement reverberated beyond Syracuse, offering a lens through which to view other weeping statue phenomena, such as the Seton Miracles in Lake Ridge, Virginia, from 1991 to 1993. At St. Elizabeth Ann Seton Catholic Church, hundreds of statues, crucifixes, and glass images of the Virgin Mary reportedly wept tears or blood, often in the presence of Father James Bruse, a priest who bore the stigmata. These events, documented by James L. Carney in The Seton Miracles: Weeping Statues and Other Wonders, drew thousands of witnesses, including Bishop John R. Keating, who observed weeping statues in his office on March 2, 1992.

Unlike Syracuse, the Diocese of Arlington declined to investigate, citing the absence of a specific divine message, and forbade public discussion, leaving the phenomena in a mysterious limbo. John Paul II’s 1994 statement, quoted in Carney’s book, provided a theological framework for understanding these events. The Pope’s assertion that Mary’s tears are a “sign” of her concern for “spiritual or physical evil” aligned with the Seton Miracles’ context, occurring amid the emerging clergy sexual abuse crisis and global uncertainties following the Cold War. Carney and others saw the Lake Ridge tears as a possible call to renewal, echoing the Pope’s view of such phenomena as invitations to holiness.

The Pope’s words also resonated with Father Bruse’s experience. Bruse, a humble priest who shunned attention, believed the phenomena were tied to the Jesus King of All Nations Devotion, which he promoted as a spiritual director. John Paul II’s emphasis on Mary’s tears as a call to conversion mirrored Bruse’s own sense that the events were meant to inspire faith, even without an explicit message. The lack of diocesan investigation, however, contrasted with the Syracuse miracle’s thorough validation, highlighting a missed opportunity to explore the cosmic significance John Paul II ascribed to such signs.

Theological and Cultural Impact

John Paul II’s statement elevated weeping statues from local curiosities to universal symbols within Catholic theology. By framing them as part of the “order of signs,” he invited the faithful to see them as divine interventions, akin to apparitions at Fatima or Lourdes, yet distinct in their silent eloquence. His reference to the tears’ historical context—post-war suffering, communism, and the Holocaust—suggested that Mary’s sorrow was not abstract but tied to specific human tragedies, a perspective that resonated with his own experiences under Nazi and Soviet oppression in Poland.

The statement also had a cultural impact, particularly in Catholic communities. In Syracuse, it solidified the basilica’s status as a global pilgrimage site, where monthly devotions and daily Masses continue to draw thousands. For the Seton Miracles, it offered a posthumous validation of sorts, as Carney and others cited the Pope’s words to argue for their significance. The statement inspired renewed calls for the Diocese of Arlington to investigate the Lake Ridge events, with petitioners citing the Pope’s recognition of weeping statues as divine signs.

A Lasting Mystery

John Paul II’s 1994 homily remains a touchstone for understanding weeping statue phenomena, casting them as cosmic cries from a mother’s heart. In Syracuse, the tears of 1953 found a home in a grand basilica, their authenticity affirmed by the Church and their meaning amplified by the Pope’s words. In Lake Ridge, the tears of the Seton Miracles remain an unresolved mystery, their potential significance left unexplored by a cautious diocese. Yet, the Pope’s vision endures, suggesting that these tears—whether in Sicily or Virginia—are not mere anomalies but echoes of a divine sorrow, calling humanity to pause, reflect, and turn toward grace.

The cosmic meaning John Paul II ascribed to weeping statues lingers in the shadows of faith, a reminder that even in silence, the Virgin’s tears speak. For those who witnessed the Seton Miracles or pray at the Syracuse shrine, the Pope’s words weave a thread of mystery, connecting the earthly and the eternal, the seen and the unseen, in a world ever in need of redemption.